In the Studio with Artist Seth Ellison

Today, we’re going In the Studio with artist Seth Ellison. Seth’s artwork is on display in the Chesapeake Arts Center’s Days of Strange Grandeur gallery exhibit, October 13 - November 23.

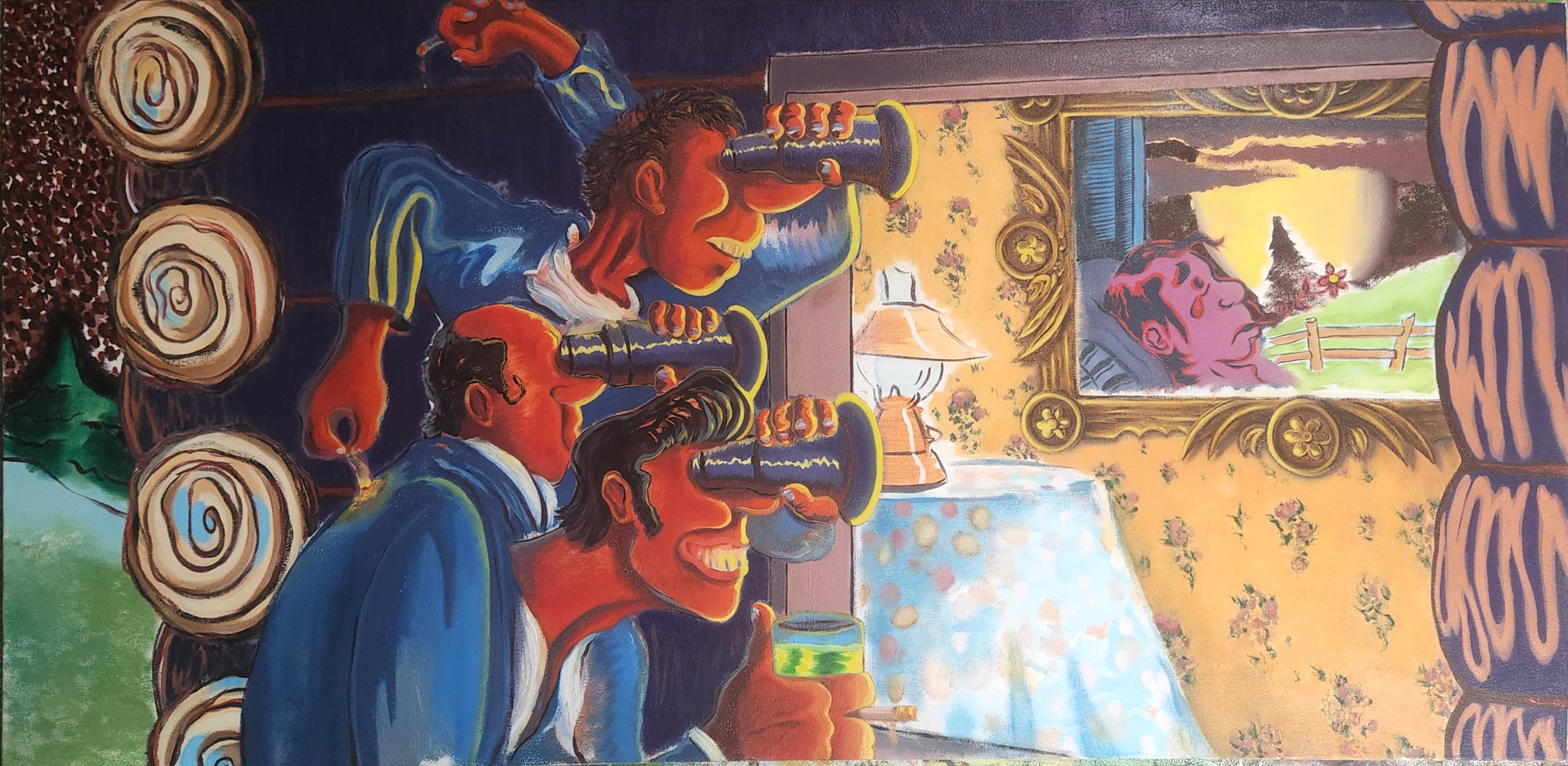

The color; the depth; the symbolism; the enormity. Your breath may skip as you enter the Hal Gomer Gallery at first glimpse of Seth Ellison’s work. Massive canvases almost completely cover the walls, every inch saturated with vibrant color. Sketchy, yet quite detailed line work is reminiscent of early satirical cartoons. Each piece of work leaves your brain reeling in an attempt to capture and decipher the copious amounts of symbolism in his compositions. Each piece varies in subject matter, but are all tied together with a common thread of southern culture.

Here’s Seth talking about his art, process and experience...

Who was your favorite mentor and what did they teach you?

As far as mentors go, there haven’t been many. I’ve always wanted one though, like Klimt was to Schiele, for example. I’ve had great art teachers, but not in the typical mentor/pupil sense that went beyond the classroom. For this reason, as a young artist I always turned to historical figures, specifically Philip Guston. What inspired me the most was how he lived his life, approaching it as a painter in everything he did.

What does your studio space look like? Where do you work and how does it affect your work?

When I moved outside of Philadelphia after grad school, I took up the master bedroom of the house as my studio. I’ve always tried to work close to my family, not only to be there when they need me, but to counter the isolation that comes with the territory. Also, my wife is my canary in the coal mine when it comes to my work. If she walks in and doesn’t say at least something about what I’m working on, I know I’ve really screwed up.

Your work has some clear nods to rural and/or southern culture, and I know you grew up in West Virginia. So, you are very intimately familiar with your subject matter. Can you talk about how your background has played into your paintings?

West Virginia is both incredibly beautiful and heartbreakingly sad, I guess like a lot of places. There is an incongruency with the natural beauty and its cultural reality, like in the Godfather when people are getting shot to classical music. That feeling has never left me and always seems to reemerge in my work.

If you could have lunch with any artist, living or historical, who would it be and why?

Are there crits afterwards? Let’s just say there are. I want to say Guston, but I like keeping him at a distance. Though it sounds painfully cliché, I would have to say Vincent van Gogh, provided he magically spoke English. I would love to know what he thought about contemporary art. Any more time with him than that and I could see it getting contentious. I might even get a “souven-EAR!” (Sorry, dad joke.)

Your work has a lot of appeal for other artists due to some of the painting and conceptual techniques you deploy. A painters’ painter, one might say. How long have you been painting? What interests you about oil paint specifically?

As a child, I was completely obsessed with Walt Disney and desperately wanted to be an animator, basically spending every spare minute repeatedly drawing duck bills and lumpy cartoon shoes. After that, I trained to be a comic book penciler, then an illustrator, and finally a painter in my early 20s. So, it goes without saying that I have surveyed a lot of different forms of art, but what grew out of that was an interest in how painting intersects with drawing. I love the idea of a versatile fluid medium, like oil paint, being somehow “defined” or “structured” by a more direct and concrete medium like drawing.

How do you know when one of your paintings is finished?

I don’t think any painting is ever truly resolved. “Finished” pieces, that I was once quite pleased with, still scream at me. I don’t want to continue working on them because I am essentially a different person. In that way, it would be almost like vandalism. I think that I know a work’s done because it achieves an inexplicable effect, a kind of metaphorical gong that reverberates through my mind. Then you have the choice: either tune that pitch or take the risk of going too far and destroying it.

Could you select one of the pieces from the exhibition and tell us more about it?

My work is an interwoven tapestry of the culture I was raised in and my own very personal experiences. Blue Summer Night is a good example. I actually worked on it for years on and off and repainted it several times. I don’t think I’ve ever struggled so much to resolve a painting. Although I don’t like to reveal my intentions in any of my works, that painting grew out of a lot of toxic masculinity that was prevalent in my formative years and the expectations certain cultures place on men and boys. For the figures in the painting… let’s just say that death is their only relief.

What was one of the most important things you had to learn in order to be able to make the work you do now?

The answer is simple: the best artists make work about their obsessions. It could be something you love or hate, but never something you are indifferent towards. In grad school, I actually threw all of my oil paints away and started making these minimalist light sculptures — a far cry from what I’m doing now. They were trendy, well received and in one professor’s assertation “chock full of potential.” That type of work might be right up another artist’s alley, but I kept having this nagging feeling that I was betraying myself. I love the nostalgic, loss, veracity, and the phantasmagoric.

What sort of interesting metaphors or symbolism do you use in your paintings that the average person might not recognize right away? Or what would people be surprised to learn about you and/or your work?

Symbolism is hiding everywhere in my work. Perhaps I use it to allow myself to say things I was too ashamed to talk about growing up because it would either offend or get the shit kicked out of me. Again, I don’t really like to reveal my magic tricks, but take for example a hat. It shows up in a lot of my work and symbolizes many things. Besides the tattered “hillbilly” hat being a stereotypical cartoon depiction of Appalachians and Southerners, it also creates anonymity, whether chosen or forced. Some of my paintings display shadows casts by hats on the faces of my characters, revealing a mysterious inner life not typically seen by the outside world, among other things.

You’ve mentioned that you are a writer in addition to being an artist. What do you write and how does it interact with your visual art (if at all)?

I’ve dabbled in just about every job a writer can get paid for. Currently, I’m a web writer, but honestly it bears no relationship to my current art practice. I have, however, kept a daily journal for many years, something I recommend to every artist. Not only will it humble you by rereading the sheer amount of cringe and pretentiousness you spew, but it allows you to cathartically process and build on your ideas.

Where do your biggest inspirations come from? Who or what is important there? Are there any specific books or other media that have been particularly impactful to you and your work?

I am constantly alluding to European old masters like Gainsborough and Millet, the American Regionalists, and even old “hillbilly” vintage postcards and comic books that saturated the U.S. in the mid-20th century. However, the primary source of my inspiration comes from memory and the actual process of making something. I usually go to the canvas with a vague notion of what I want to do, not because I’m lazy or devoid of ideas, but to get out of my own way and let the process take over. It’s a symbiotic dance between my consciousness and the material.

What advice would you give to younger artists?

Maybe more of a warning than advice: You’ve got to have the will of the devil.

For more information on Seth and his artwork, check him out on Instagram or on his website.

Days of Strange Grandeur Gallery Exhibition

October 13 - November 23

Opening Reception: October 13 | 6-8pm

Gallery Hours:

Monday-Thursday 10am-6pm | Saturday 10am-1pm